Survival Stories

Survival Skills Revived: Bison Hunt with Handmade Bows in Texas

In the realm of self-reliance, you’ll encounter a myriad of strategies for survival should our everyday systems cease to exist. Some individuals advocate for stockpiling essentials, anticipating a time when convenience transforms into chaos. Others propose hiding supplies in various locations, staying one step ahead of potential threats. There are those who promote self-sustenance through farming, urging a return to the land. And then, there’s the solitary survivalist, ready to channel their inner woodsman, rifle in hand, confident in their ability to survive indefinitely using primitive wilderness survival skills.

However, no strategy is foolproof. Reality often scoffs at our best-laid plans. A brief look back at 2020 illustrates just how fragile our interconnected world is, and how even the most detailed plans can fail. What if we were stripped of our supplies and modern tools? What does starting from scratch truly entail, and how can we, like our ancestors, transform raw nature into essential tools?

Enter Phillip Leibel, a man seemingly carved from the wilderness itself. A familiar face on History Channel’s ‘Alone: The Beast’, Phillip is a master of primal craft and the driving force behind Primitive Wilderness Survival. His mission is to revive the forgotten skills of ancient cultures and pass that knowledge on to those eager to learn. His latest venture is a workshop where participants can learn to craft bows in the Cherokee tradition, culminating in a hunt against the formidable bison. We were fortunate enough to secure a spot in his course, which took us to Graham, Texas, a treasure trove of insights.

Graham, Texas is somewhat off the beaten path, making it the perfect location for a company like Primitive Wilderness Survival. Here, away from the hustle and bustle of city life, one can truly disconnect from the technology that permeates our daily lives. Upon arrival at a ranch on the outskirts of town, we joined several other like-minded individuals, all eager to learn the fundamental principle of self-reliance: creating something from seemingly nothing. Students traveled from all over the country, each with unique backgrounds and varying skill levels. Some were familiar with making primitive tools, while for others it was their first time.

Our instructor, Phillip, welcomed us warmly and encouraged everyone to settle in for a nine-day immersive experience. As we set up camp among the juniper, cedar, and locust, Phillip took the time to get to know each member of his class. He reminded us of a proverb about community and collaboration that goes, “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” With this in mind, Phillip began the first day by encouraging us to think of each other as a tribe, to help each other along the way, and to foster an environment of mutual respect.

The concept of forming a tribe was not just a lesson, it was our new reality. Humans are social creatures, and while we often romanticize the idea of going it alone, that scenario seldom ends well. However, if we can organize as a group of like-minded individuals (a tribe), we can work towards common goals with greater enthusiasm and tenacity. This would become increasingly important as the course progressed, especially when it came time to hunt one of the largest creatures of the North American continent.

In honor of Phillip’s cherished Cherokee roots, our session began with a dive into tradition. We would be hand-crafting a bow-staff in the Cherokee style, using the sturdy osage orange wood. Before we even touched the wood, we learned about the art of seasoning—a process that requires patience, as the wood is left to dry out naturally until it’s ready for crafting. This process doesn’t happen overnight. Seasoning timber the old-fashioned way involves leaving it exposed to the elements rather than rushing the process in a kiln. It’s a slow dance with time, often taking over a year. Fortunately for us, Phillip, ever the foresighted craftsman, had a stash of these time-tempered pieces ready for us to begin our crafting journey.

Every bow is a custom creation, tailored to the individual who will wield it. As such, you must know the exact tension required as the string draws an arrow back. This isn’t a trivial fact to be overlooked—it’s the core of the craft, guiding the bow’s optimal height and thickness. To master this, we used a completed bow and an arrow, marked with inch marks along its spine, to measure our natural draw length. It was similar to taking a measure of your reach. While there are many opinions on the ideal length of a traditional bow, for our purposes, we settled on a simple method. We measured how far we could comfortably draw the arrow back. It’s a technique that’s less about numbers and more about feeling, finding that sweet spot where the bow feels like an extension of your own body.

Determining the perfect length for the bow was just the beginning. Next, we began to carve the Osage orange, carefully shaping it into the silhouette of a traditional Cherokee bow. One wise piece of advice we received from a fellow tribesman was, “Carve away anything that isn’t a bow.” This initially seemed cryptic, but it was spot on. Traditionally, one might have used stone tools for this delicate process. We were fortunate enough to have draw knives and rasps on hand. But even with these modern conveniences, the task was a marathon. With each shaving of wood, we balanced on a knife’s edge. Too much left, and the bow wouldn’t bend, too little, and you’d hear the heartbreaking crack of failure. As the sun set on the first day, we were still chipping away, not quite there yet.

The light of the second day ushered in an even finer dance with detail. As the bow’s shape neared perfection, the coarse tools were traded for cabinet scrapers and sandpaper. Every so often, Phillip would test our progress on his trusty tillering jig—our efforts being put to the ultimate stress test. If things did not appear quite right, back we’d go, scraping and smoothing. Each trial was a pulse-quickening moment, wondering if our creation would hold or shatter. But the seasoned osage orange, tough as nails, didn’t let us down. We kept on, tillering and sanding, painstakingly inching towards a bow that felt just right in our hands, tailored to our own pull and power.

No bow can launch arrows unless it has a string. Our ancestors made bowstrings from sinew, braiding it into lengths sufficient for strings—meaning they meticulously removed strips from large animals or intertwined shorter lengths, hoping the intense strain wouldn’t snap or untangle the braid. Today, for ease and security, we use a cord called B-50. This synthetic rope has remarkable tensile strength and is favored for crafting traditional bowstrings.

To make a string of the proper thickness, we intertwined six strands each of two colors (totaling twelve strands) using the reverse-wrap technique. One end is woven into a loop secured by notches at the bow’s end. The other end is tied by hand, allowing adjustments to the string’s length according to the chosen draw length and tension. For some, this braiding posed a significant challenge, while others, blessed with nimble fingers, managed it with less difficulty. Fortunately, as members of a tribe, we could ask for help from the more skilled in exchange for assistance with tasks like bow contouring. This collaboration sped up our progress beyond what we could have achieved alone.

Various materials can make a decent arrow shaft. Phillip notes the Cherokee preference for river cane, but we used bamboo tomato stakes from a nearby garden shop as a handy substitute. A suitable arrow shaft can be any material with the right diameter and either naturally straight or adjustable to be straight. We each selected five or six relatively straight pieces, then gathered by the camp’s central fire to refine their alignment.

Looking down the length of the bamboo, its bends and twists become apparent. Brief exposure to the fire’s heat softens the fibers, providing a short window of time to straighten the shaft, easing out curves. It’s a delicate balance—enough force to ensure it sets straight once cool, but not so much that it snaps. Occasionally, bamboo with preexisting flaws would crack, despite our caution. Phillip reassured us, it’s better for flaws to reveal themselves now, rather than during a high-tension launch from a bow.

With our shafts straight, we addressed the bamboo’s nodal bulges. Using rasps and sandpaper, we worked each one down to achieve a uniform diameter from end to end. Phillip reminded us that in a more primitive setting, this step would involve coarse stones and significantly more elbow grease.

Feathers are essential for stabilizing an arrow in flight. Modern arrows often sport two or three fins made from a slender polymer. For our projectiles, we chose a pair of feathers, either turkey or goose, to flank the shaft. These quills must be sculpted to work together, ensuring optimal aerodynamic stability. Their silhouette typically mirrors that of a rocket fin yet can be tailored to the archer’s liking. While many opt for scissors to carve the desired profile, the application of heat via a heated rock or blade can sculpt the feathers just as well.

To secure the feathers, we used dampened sinew strands interlaced with adhesive—no intricate knotwork necessary. Phillip explained the traditional method of making and applying hide glue for such tasks. However, our modern shortcut involved quick-setting wood glue. Once set, the fletching is remarkably rigid, resisting any attempt to dislodge it with sheer force.

As for the arrow’s leading segment, we calibrated it to be weight-forward by embedding weights within the bamboo’s inner circumference. Phillip shared wisdom on the use of sand or clay for weight, enhancing the arrow’s impact and in-flight stability. In our case, to maintain momentum in our workshop and to ensure a forceful impact, we substituted sand or clay with metallic rods, sparing us the laborious task of maneuvering granular or sticky substances into the bamboo’s narrow bore.

Armed with a bundle of our straightest and best-fletched arrows, we moved towards the range for an impromptu accuracy test. Our target was a rustic round hay bale, its center marked by a crimson bullseye. This exercise also served as a practice for bow stringing, a mildly cumbersome skill to master given the osage staves’ reluctance to bend. We were all amazed at how powerful our handmade creations were at this point, easily comparable to a modern traditional-style longbow.

A brief period passed before the erratic flyers—victims of imperfect straightening or feathers—were singled out, leaving behind those arrows that reached the bullseye’s vicinity with remarkable consistency. For a few among us, a pair of trusty shafts sufficed. Yet for others, it presented an opportunity to make a small adjustment to the feathers or a twist to the spine. Those deemed true were meticulously segregated, ready for the progression to the next stage.

Four days had passed, and though we had worked from dawn to dusk (a few of us even honing our archery in the pitch black, guided by headlamps), a significant challenge still loomed. We aimed to craft an arrowhead, primitive yet sharp enough to pierce the tough skin of a prime bison. Phillip taught us the art of stone knapping, a technique crucial to our ancestors.

Stone knapping is a skill that takes years to master, and the prospect of gaining enough proficiency to successfully produce an arrowhead within a single day is nothing short of intimidating. However, Phillip, alongside tribe members seasoned in knapping, provided an exceptional introduction to the basics. We learned how strategic strikes create ripples in the rock’s crystalline lattice, splitting off smaller fragments from the larger mass. Certain stones yield better results, and for our lesson, we chose from a range of obsidian, chert, and even glass bottle bases.

With shards in hand, we undertook the painstaking task of whittling them down to arrowheads, sliver by sliver. The tools are aptly named for their purpose—a ‘flaker’, tipped with copper and similar in profile to the head of a marker, is for chipping away precise fragments. ‘Boppers’, copper-domed ends fixed on dowels, serve to detach larger sections and smooth out jagged edges. A robust slab of hide protects our legs, serving as a workbench for this delicate operation. Mastery of knapping is a gradual ascent which exceeds our limited time frame, yet under Phillip’s and our skilled companions’ tutelage, we edged closer to fashioning something that resembled the silhouette of an arrowhead.

To make arrows lethal for felling a formidable bison, arrowheads need to be firmly attached to their shafts. This is achieved by making heated pine pitch—a mixture of pine resin blended with the fibrous droppings of deer—within stone vessels positioned next to a fire. If the pitch gets too hot, it is prone to catching fire since its flashpoint is low. A recess is meticulously chiseled into the shaft, precisely sized to accommodate the base of the arrowhead, and the heated pitch is used as an adhesive to secure the arrowhead in its niche. Afterwards, a mixture of wood glue and sinew is used to lash the arrowhead firmly, ensuring its integrity upon discharge from the bow. With the assembly of arrows and the stringing of bows, only one step remained: to track and bring down the massive quarry.

As the evening unfolded before the anticipated day of the hunt, our campfire glowed, a testament to a week’s diligent efforts. We exchanged hearty praise over each other’s bowmanship and eagerly speculated about the forthcoming pursuit. Our conversations stretched into the night, our eyes drawn upward as a shroud of clouds covered the stars, while the distant rumble of an approaching thunderstorm provided a backdrop to our gathering. Hunkering down for the night, we all fell asleep in our tents thinking about the next day, wondering how it would play out.

The morning after the storm, a mist had claimed our encampment, kicking off hunting day under overcast skies and the promise of residual showers. Before setting out for the territory where we would embark on our quest, Phillip gathered us together for a ceremonial pre-hunt observance. Arranged in a crescent formation, the moment to express reverence for the life we were set to claim was upon us. In nature, an animal such as the bison might meet a grisly fate, falling prey to the savagery of the food chain, often only after a battle with the infirmities that come with old age, sickness, or injury. On this day, we aimed to honor its spirit, bringing its life to a swift and compassionate end. Our ritual concluded with the cleansing aroma of juniper and the purifying essence of sage, a ritual to obscure our presence from the keen senses of our quarry.

As it turned out, the hunt did not go quite as planned. Bison are incredibly intelligent, clever animals, and the one we were hunting made us work exceptionally hard for it. The hunt itself lasted a day and a half, despite our tribe of eight (and the rancher who owned the property) tenaciously pursuing it. Our quarry defied our expectations at every turn. It never set a pattern, never reacted the way we thought it would, and never moved to where we were trying to drive it. Over the course of the hunt, we watched it jump over six-foot high fences, leap over cattle traps, and even use cattle herds as cover. In the open, it never let us get close enough to take a shot. Concealed in woodland, it tread silently on the forest floor, gliding effortlessly through dense underbrush that impeded us. Sometimes it seemed to vanish into thin air, forcing us to regroup, devise new strategies, and begin tracking all over again.

Eventually, after much frustration and many miles of active tracking, stalking, and hunting, our tribe maneuvered it into a position where it could be safely harvested. For some it was a joyous relief, for others it was a poignant and emotional end. But no matter how everyone felt upon the culmination of our efforts, we were all proud of the work we had put into in, and grateful to have gone through the experience with such an amazing group of people.

The idea of living directly from the earth often sparks curiosity. We might lose ourselves in films like ‘Dances with Wolves’ or the historical narratives of trailblazers like Lewis and Clark. Imagining ourselves in their shoes, it might seem feasible to emulate their existence. However, the theatre of the mind is vastly different from tangible existence, and the cultivation of skills that our ancestors mastered with apparent ease demands both relentless dedication and time. Our time spent with Primitive Wilderness Survival is testament to this. We took many shortcuts by substituting stone tools with steel, and other modern amenities, otherwise the course could have easily taken twice as long.

Understanding the extent of challenges our distant predecessors endured to thrive solely on nature’s offerings cannot be accurately gleaned from the passive acts of reading, or watching tales unfold on screen. I confess, my initial assumptions about the labor involved were naive until I engaged in the actual process of fashioning a hunting implement and the subsequent endeavor to procure game with it. My enlightening journey alongside my tribesmen, and Primitive Wilderness Survival’s expert instructor Phillip Liebel, illuminated the astonishing resourcefulness intrinsic to humanity, and the formidable force of collective minds striving toward a shared objective.

To answer the question of whether living solely off the land is possible, the answer is a resounding ‘yes’. Yet the difference between surviving to thriving hinges on whether one chooses solitude, or the fellowship of a tribe of like-minded individuals, unified by purpose. Immersing oneself in the study of primitive skills reveals just how important and intertwined humanity is with another, and during these tumultuous times, it is worth rediscovering that important truth.

Our Thoughts

I found this article particularly enlightening. It’s one thing to theorize about survival in a post-apocalyptic world, but another to actually experience it. The writer’s journey from crafting his own bow to hunting a bison was a vivid illustration of how challenging and rewarding self-reliance can be.

Phillip Liebel’s Primitive Wilderness Survival course sounds like an amazing opportunity to learn from a true master. It’s clear from the writer’s account that his techniques and teachings are deeply rooted in tradition and respect for the natural world.

The emphasis on community and cooperation throughout the experience was refreshing. In a world where individualism is often glorified, it’s a powerful reminder of the strength that comes from working together towards a common goal.

The writer’s reflection on the difference between surviving and thriving was also thought-provoking. It’s clear that self-reliance doesn’t mean going it alone, but instead learning to work with others and with nature itself.

In conclusion, this article has reinforced my belief in the importance of being prepared and the value of traditional survival skills. It’s a reminder that we are all capable of more than we know, and that the knowledge of our ancestors can still serve us well today.

Let us know what you think, please share your thoughts in the comments below.

Survival Stories

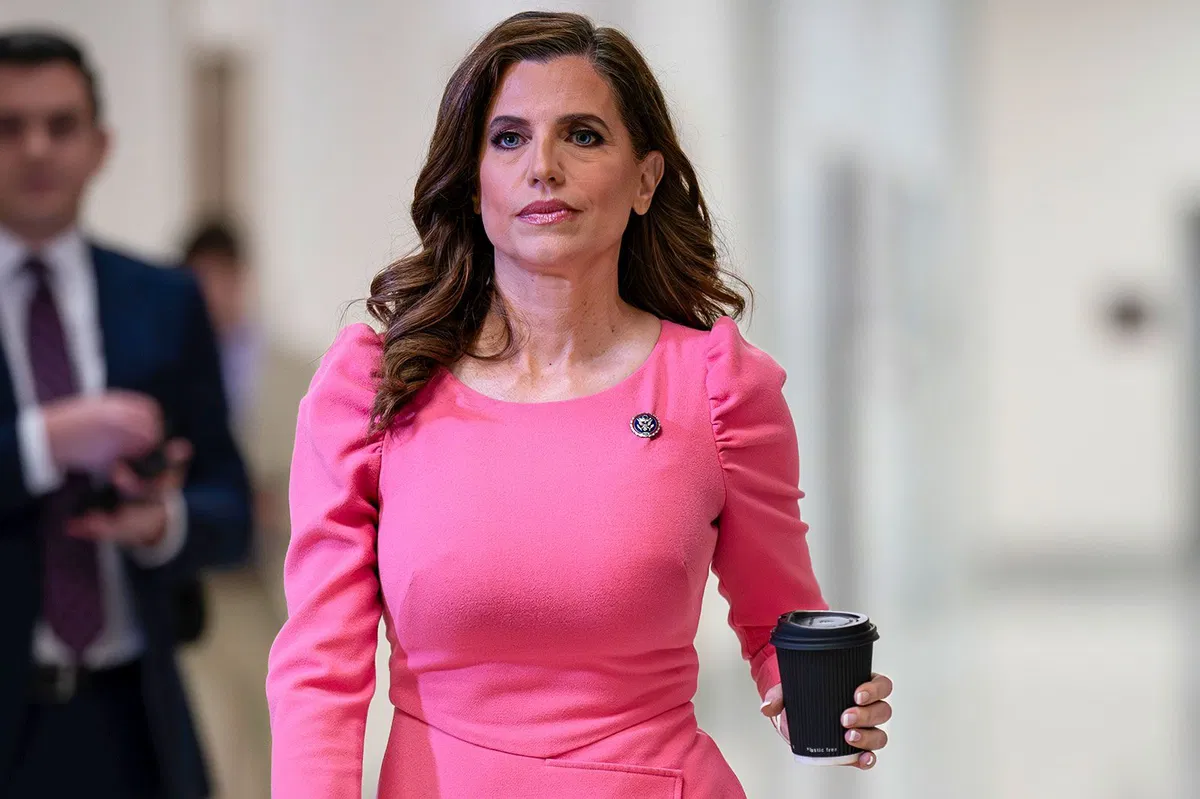

Rep. Mace’s Capitol Encounter Sparks Controversy and Legal Battle

James McIntyre, a 33-year-old from Illinois, has pleaded not guilty to a misdemeanor assault charge following an incident involving Rep. Nancy Mace on Capitol grounds. The alleged encounter occurred on a Tuesday night, leading to McIntyre’s arrest for reportedly assaulting a government official.

The incident unfolded when McIntyre approached Rep. Mace and offered to shake her hand. According to a police affidavit, two witnesses observed the interaction and described McIntyre as a man in his forties. When Mace extended her hand, McIntyre allegedly clasped it with both hands and “shook her arm up and down in an exaggerated, aggressive hand shaking motion.”

Witnesses managed to identify McIntyre through an internet posting, providing his name and photo to the U.S. Capitol Police. Mace corroborated the witnesses’ accounts, stating that she attempted to withdraw her hand but was unable to do so. She reported feeling intimidated and experienced pain in her wrist, arm, and shoulder following the encounter.

During the aggressive handshake, McIntyre reportedly stated, “Trans youth deserve advocacy.” Mace refrained from responding during the incident, later expressing her shock and discomfort.

After the event, Mace took to social media to inform her followers of the situation.

“I was physically accosted tonight on Capitol grounds over my fight to protect women. Capitol police have arrested him,” Mace shared in a post on X. “All the violence and threats keep proving our point. Women deserve to be safe. Your threats will not stop my fight for women!”

She continued to discuss the incident on social media, revealing in one post that she had spoken with President-elect Trump.

“Thank you, Mr. President, for checking in on me and standing up for women,” Mace wrote. “We cannot wait to see you back in the White House.”

In another post, she shared an image of herself with her arm in a sling, highlighting the physical impact of the encounter.

The incident comes amidst Mace’s outspoken opposition to transgender individuals using bathrooms that do not align with their biological gender. She has been particularly vocal against Rep.-elect Sarah McBride, a Democrat from Delaware, using the women’s restrooms on Capitol Hill.

Mace has reported receiving death threats and feels she is being “unfairly targeted” for her stance. Her proposed resolution, H.R. 1579, aims to restrict bathroom use in the House to facilities matching one’s biological sex.

Following McIntyre’s arraignment in the Superior Court of the District of Columbia, a magistrate judge ordered his release. Meanwhile, Mace’s office has not provided an update on her condition.

Let us know what you think, please share your thoughts in the comments below.

Survival Stories

Unseen Advantage: Law Enforcement’s Rapid Adoption of Optics

In the world of law enforcement and survival, the ability to quickly and accurately assess a situation can make all the difference. This is why the rapid adoption of optics by law enforcement agencies is hardly surprising. These tools provide a wealth of visual information, aiding in making more informed decisions. A key factor in the selection of these optics is the window size, but it seems that co-witness sights, which can sometimes occupy half of the entire optic window, often don’t receive the attention they deserve.

“Without question, the speed with which LE agencies have adopted optics is testament to the advantage they offer: more visual information that yields better decisions.”

Interestingly, suppressor height sights are frequently paired with optics. To comprehend why this particular sight remains a popular choice when selecting co-witnessing sights, we must journey back in time. Around 2009, shooters, both professional and non-professional, began to repurpose a solution initially designed for Close Quarters Battle (CQB) rifle work for use on pistols.

The Trijicon RMR, a compact electronic optic, was a welcome alternative to the larger optics typically seen on competition pistols. Its smaller size offered more holster options, less likelihood of snagging in the field, and a more robust window and housing. As a result, it addressed many of the issues raised by professional users, leading to a shift towards an optics sighting solution within the firearms community.

“The smaller footprint meant more holster options, less to get caught on while in the field, and a less delicate window and housing.”

This shift was spearheaded by individuals in the military, law enforcement, defensive firearms instruction, and competition professionals. With the introduction of these optics, performance improved, and new shooters were able to develop accuracy and speed more quickly. The instinctual focal plane response to stress, which previously had to be trained out, could now be utilized as an asset by Firearms Instructors working with students who had optics on their pistols.

“Performance increased, accuracy and speed developed sooner with new shooters, the intuitive and instinctual focal plane response to stress no longer needed to be trained out—and instead, the threat-focus could now be an asset used by Firearms Instructors working with students who had optics on their pistols.”

As the popularity of optics grew, the aftermarket and firearms manufacturers responded by supporting this “new” sighting system. However, one critical component of the system was often overlooked: the back-up sights. This oversight highlights the need for a comprehensive approach to firearm optics, one that considers all elements of the sighting system to ensure optimal performance and safety.

Our Thoughts

The adoption of optics in law enforcement is a testament to the technology’s effectiveness. It’s no surprise that tools that enhance visual information, thus enabling better decision-making, have become a staple in the arsenal of law enforcement agencies.

The rise of the Trijicon RMR is particularly noteworthy. Its compact size and robust design addressed many of the practical concerns of professional users, leading to a broader acceptance of optics as a sighting solution.

The benefits of these optics extend beyond their practicality. They have brought about a shift in the training of new shooters, turning the instinctual focal plane response to stress into an asset rather than a hurdle to overcome. This has undoubtedly contributed to the improved performance observed among new shooters.

However, the focus on the main optic often results in the neglect of back-up sights. This is a reminder that a comprehensive approach to firearm optics is necessary to ensure optimal performance and safety. After all, a tool is only as good as the system supporting it.

Let us know what you think, please share your thoughts in the comments below.

Survival Stories

Mental Resilience: The Overlooked Key to Survival Success

In the realm of survival, we often focus on the physical aspects: the gear, the skills, the terrain. Yet, one crucial element often overlooked is our mental health. As a seasoned survivalist and a licensed mental health therapist, I’ve experienced firsthand the importance of mental resilience in a crisis.

I recall an incident during my first exploration of Red Rock Canyon. The vast, humbling landscape was a sight to behold, but it was also a formidable challenge. Despite my preparations, I found myself lost on a wild game trail, far from the intended path.

“Okay, no big deal,” I reassured myself. “I’ll just retrace my steps.”

But the creeping sense of panic was undeniable. I was low on water, surrounded by thick brush, and far from any signal. It was in this moment that my mental health training became as crucial as my survival skills.

“If anyone can figure this out, I can.” I thought. Or rather, tried to convince myself….

The human brain has a built-in survival mechanism known as the fight-flight-freeze response. When faced with danger, our heart rate increases, our pupils dilate, and our breathing becomes rapid. While these physiological changes can enhance our strength and speed, they can also lead to panic attacks, which can be detrimental in a survival scenario.

Soldiers and first responders are trained to manage this response, and so can civilians. Understanding mental health first aid can be a lifesaver in personal emergencies or when trying to calm someone else in a crisis.

“Okay…” I thought, “let’s just backtrack a little. See if I can’t find the main trail.”

I remembered the acronym S.T.O.P., taught in wilderness survival classes: Sit, Think, Observe, Plan. I sat down, focused on my breathing, and began to regain control of my racing thoughts.

“Breathe.” I thought. “In through the nose, slow. SLOW. Hold it for a few seconds. Now release through the mouth even slower. Pause. Repeat.”

I knew I had to control my thoughts to improve my feelings and make good decisions. Catastrophic thinking like “I’m gonna die” or “What if a rattlesnake bites me?” could trigger panic mode.

“Okay, what do we know?” I thought. “I know I can’t be too far off-course, no more than a couple miles. I know a few people knew generally where I was going (but not the specific trailhead) and that I expected to be back by nightfall. I know I have survival training and some kit with me that would help me make it through the night if needed. I can do this.”

After observing my surroundings and assessing my resources, I made a plan. I decided to head in the direction of what I believed to be a road, using a large branch to tap the ground in front of me to ward off any potential rattlesnakes.

In the end, I made it back to my vehicle without having to spend the night in the desert. The experience was a stark reminder of the importance of mental health in survival situations.

In the aftermath of a crisis, people will be in panic mode. Knowing how to guide someone through the stresses of a crisis can help mitigate some of the negative effects of traumatic events.

First, ensure the scene is safe. Then, assess the group, find helpers, and triage the situation. Ground the person by asking them to describe their surroundings and their feelings. Encourage slow, deliberate breathing and validate their experiences.

Long-term effects of repeated activation of the fight-flight-freeze response can include panic attacks, nightmares, and flashbacks. If you’re prone to these symptoms and find the techniques described here aren’t helping, consider seeking help from a licensed therapist.

Remember, it’s not a matter of being weak or strong. Some of the bravest individuals I’ve worked with have sought therapy for their symptoms. It takes great strength and bravery to ask for help.

Since my experience in Red Rock Canyon, I’ve incorporated mental health first aid and awareness into my survival teachings. I’ve also adjusted my approach to hiking, ensuring I communicate my exact route and expected return time, carry more water, and stay focused on the trail.

Survival isn’t just about the physical. It’s about the mental too. And with the right skills and mindset, we can navigate any crisis with resilience.

Our Thoughts

This compelling account underscores the often overlooked but critical role mental health plays in survival scenarios. The author’s experience in Red Rock Canyon drives home the importance of not just physical preparation, but mental preparedness as well.

The fight-flight-freeze response, while instinctual, can be detrimental if not properly managed. As survivalists, we should heed the author’s advice and learn to control this response, much like soldiers and first responders are trained to do.

The S.T.O.P. method is a useful tool in regaining control of our thoughts and feelings in high-stress situations. It’s not just about physical survival skills, it’s about mental resilience and clarity of thought.

Moreover, the importance of understanding mental health first aid cannot be overstated. It can be a lifesaver, not just for ourselves, but for others in crisis.

Ultimately, the author’s story is a reminder that survival isn’t just about the gear, the terrain, or the skills — it’s about the mind too. And in the face of adversity, with the right mindset, we can navigate through any crisis with resilience.

Let us know what you think, please share your thoughts in the comments below.

-

Tactical1 year ago

Tactical1 year ago70-Year-Old Fends Off Intruder with Lead-Powered Message

-

Tactical1 year ago

Tactical1 year agoVape Shop Employee Confronts Armed Crooks, Sends Them Running

-

Preparedness11 months ago

Preparedness11 months agoEx-Ballerina’s Guilty Verdict Sends Tremors Through Gun-Owner Community

-

Preparedness9 months ago

Preparedness9 months agoGood Samaritan Saves Trooper in Harrowing Interstate Confrontation

-

Tactical1 year ago

Tactical1 year agoMidnight SUV Theft Interrupted by Armed Homeowner’s Retaliation

-

Survival Stories2 years ago

Survival Stories2 years agoEmily’s 30-Day Experience of Being Stranded on a Desert Island

-

Preparedness10 months ago

Preparedness10 months agoArizona Engineer’s Headless Body Found in Desert: Friend Charged

-

Preparedness10 months ago

Preparedness10 months agoBoy Saves Dad from Bear Attack with One Perfect Shot

Kenneth Lauer

April 13, 2024 at 2:31 pm

Wonderful article. Full of mind opening thought. Thanks for the adventure.